Articles

The Purpose of the Arts

Many students, especially freshmen who must oblige at least one semester of an art elective, may wonder what the point of the arts is—studio art, theater, guitar… for what? The question is especially valid when a high schooler’s time and the school’s resources can be allocated to other, seemingly more fruitful endeavors, say rigorous athletic programs that secure championship banners or clubs that equip students with real-world, professional opportunities. The arts can be easily cast aside as a “weak” science, a discipline designated for those who are overtly emotional or lonely, or crazy. But art has been, since the beginning of civilization, a demonstration of human excellence and sophistication. And although our social landscape has changed, the chance to uncover some of our greater human faculties lies only beyond the gates of art’s creation. That is worth at least one semester of freshman year, no?But specifically, why art?Art floods life with newfound meaning. At some point in life, humans come to contemplate a greater meaning for themselves. Psychologists often deem this a transition from the concrete to the abstract, when the human mind is no longer content following society’s imposed structure, and turns within to seek deeper meaning. Painting on caves wasn’t the most practical thing for cavemen as they were clinging to their thread of survival, but they did it anyway. Ludwig van Beethoven lost the ability to hear his music in his twenties, but he continued playing the piano until his death at age 57. Van Gogh died penniless and unknown, but still he painted. If you asked the creative geniuses why they pursued art, they would not just respond “because I enjoy it”. For artists, creation is a compulsion when life becomes too mundane. If you asked Picasso, he would say, “The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.”Art is a craft that demands virtue. Playing sports is a good parallel. Maybe you began playing a sport because it was fun in the backyard or looked cool on TV. But then you began playing it more seriously and steadily grew a resolve to become great. So you spent time working out, building skill, and thrusting yourself in the most competitive environments. By the end of your time playing the sport you’ll realize that you weren’t just playing a sport: you were building virtue. You became a better athlete but you also became strong, consistent, resilient. Art is no different. Renaissance artists around the 15th century desperately wanted their work to appear more realistic and magnificent, so they studied anatomy, geometry and nature with insatiable drive. Michelangelo craned his neck atop tall scaffolding for four years to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Being any form of artist innately requires extreme devotion, concentration, patience, and feeling. If you want to become an unshakably focused person that perceives the world with more power, art may be the discipline for you.Art makes beauty permanent. In its more classical form, art became a way to glorify life. Historically, this has taken the form of a 17-foot tall statue of an idealized David (also by Michelangelo), magnificent churches that tried to build heaven on Earth, and books of musical scores pouring out delicate sonatas. I sometimes try to imagine what Michelangelo felt after seeing the object of his four year long, single-minded work complete. Beauty has been surely achieved when you can take a step back after a long day and proudly say, “I made that.” Beauty is goodness and goodness is beauty. As the writer Fyodor Dostoevsky promises, “Beauty will save the world.” At some point, creation goes beyond preserving the best of the human experience; at some point, it transcends it. When that day comes, the artist lives through their work and their work lives on for them. The English poet John Keats captured this idea when he wrote, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.”Art is necessary for humanity. John Keating, the character from Dead Poet’s Society who has stolen the hearts of audiences worldwide, would add the following about literature: “We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion… Medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, love—these are what we stay alive for.”An interaction involving the famous world leader Winston Churchill upholds the necessity of art in a rather unexpected setting: the most depressing days of World War II. When Churchill’s advisors urged him to cut funding for art in the hopes of alleviating the dire state of Britain’s economy, he supposedly responded: “Then what are we fighting for?”So I’ll ask you the same question: if not to seek meaning, what are you fighting for? If not to build virtue, what are you fighting for? If not to preserve beauty, what are you fighting for?If you haven’t explored the world of art, what are you waiting for?

About Me

My name is Aarav Jain, and I started this business to share my artistic expression of life’s depth with a broader audience. In the last few years, I’ve grown increasingly unwilling to conform to the mundane, cyclical, and too often futile routines imposed by society. This curiosity led me to study the creative geniuses—from Michelangelo and van Gogh to Shakespeare. Guided by their brilliant pursuits of truth, I have spent my own inspired nights painting and searching for answers. These spontaneous, fervent moments have revealed two simple truths to me: 1) Art is a science that reveals beauty, and 2) there are deeper truths to human life that can be most fittingly realized with paint on a canvas.

Art Gallery

Written Explanations

"Painting is just another way of keeping a diary."

-Pablo PicassoIn this section, I am preserving documentation of the thought process behind some of my most meaningful works of art. Many concepts for my art are derived from daily thoughts: whether journaling, writing poetry, or general contemplation. Ultimately, I hope that my art can serve as a method of communication for some of my strongest personal convictions.Of course, my intent should only guide your interpretation of my work. In art, the viewer must decide what message is most pertinent and powerful to them. Consider my work an invitation for personal reflection.Click to read below:

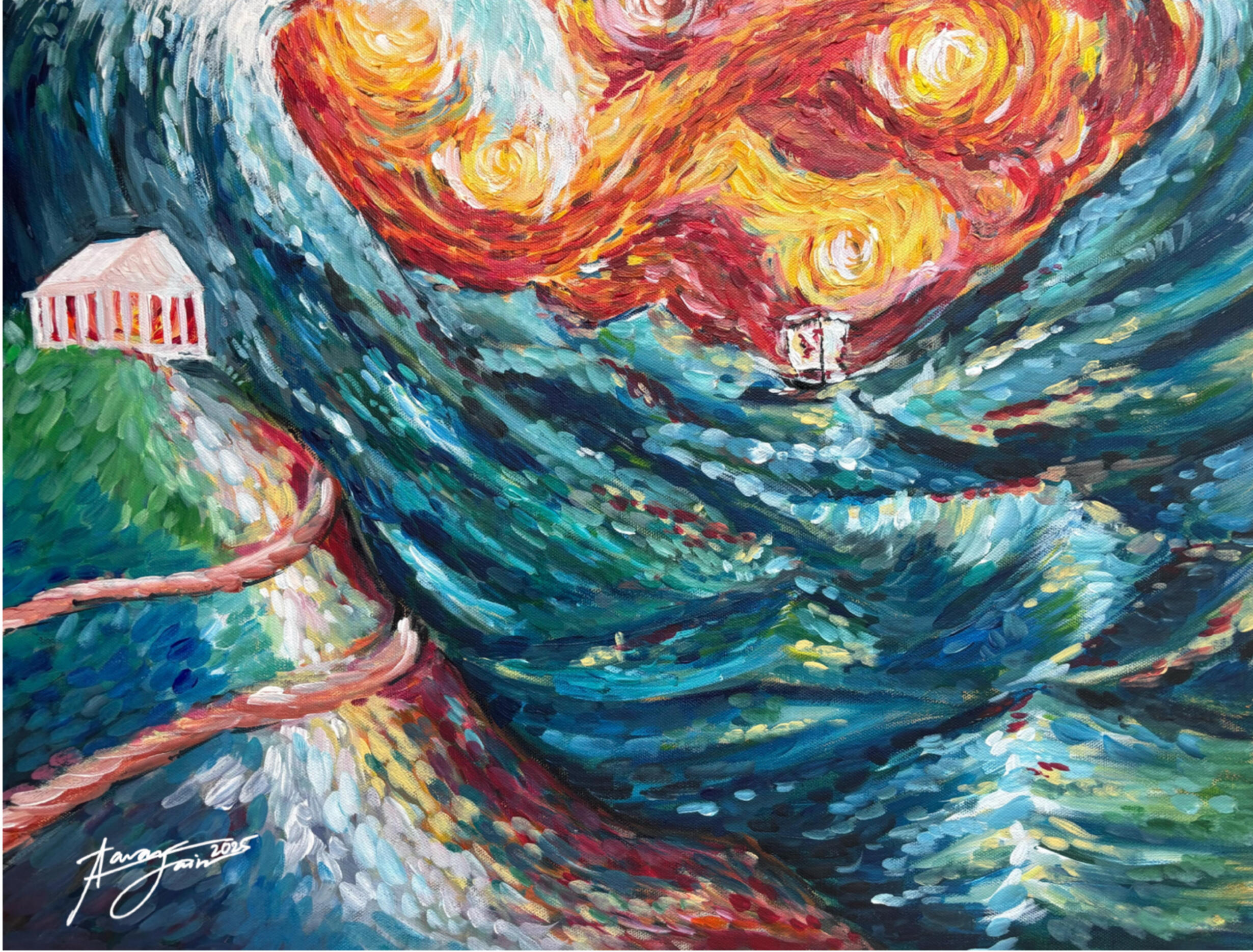

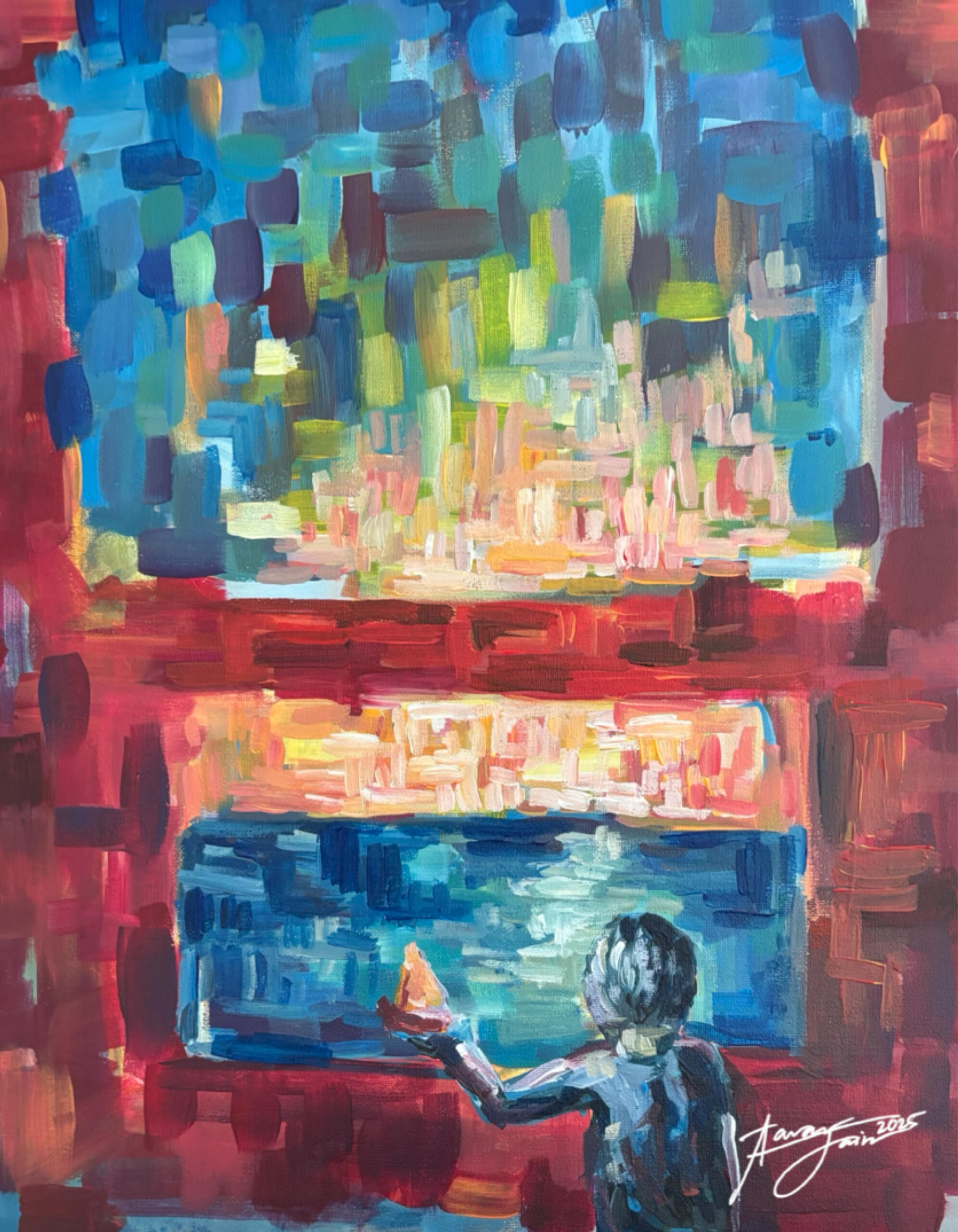

Ship to Sea

The idea of this painting is to communicate the dichotomy between youthful innocence and a cutthroat world. Children, in their curiosity, make toy ships. But soon, they’ll learn to design real ships to weather life’s storms. Both have beauty: the magnificence of the sea and the obliviousness of the child.A brilliant expression of this concept comes from JD Salinger’s book The Catcher in the Rye. When the main character finds himself out of place in school and the superficial, disingenuous world surrounding him, he dissolves into what may appear as insanity. Still, when asked what the purpose of life is, his example resounds with clarity. He says that in a perfect world, he would like to live on a rye, where children play freely. And if they ever fall off the cliff, he would like nothing more than to catch them. This gives the book its title: The Catcher in the Rye. Too often are the sparks of youth extinguished by the dullness of the real world.But perhaps, with a little bit of intent, we can rekindle the brilliance of our truest curiosities and passions. Sometimes, we take life for granted: the joy of waking up, seeing the sun, driving to school or work. And too often, it’s only in hindsight that we enjoy these things. Starting with today, here is your reminder to experience the simplest joys of life in the most feverish ways. Become the child again.

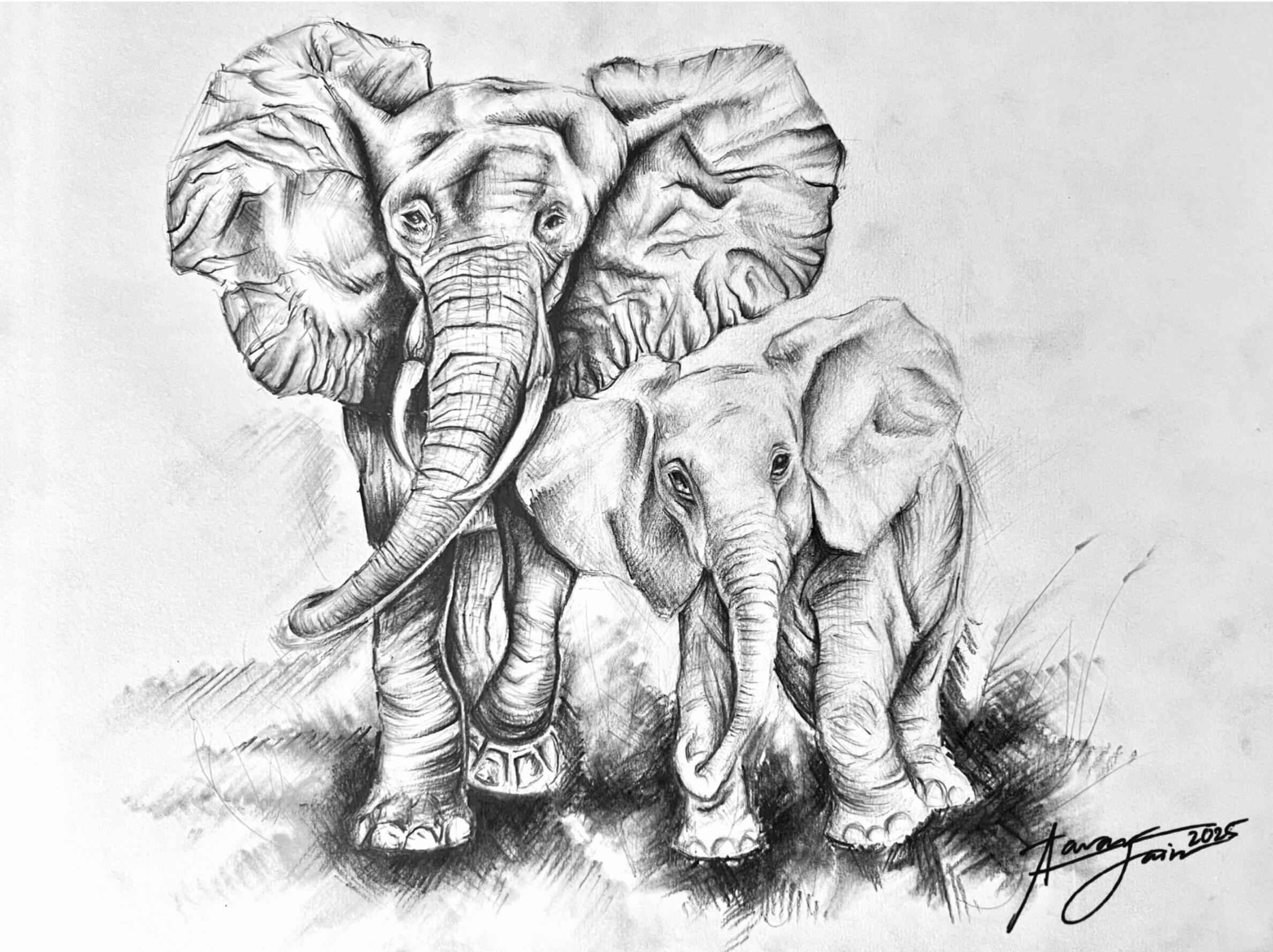

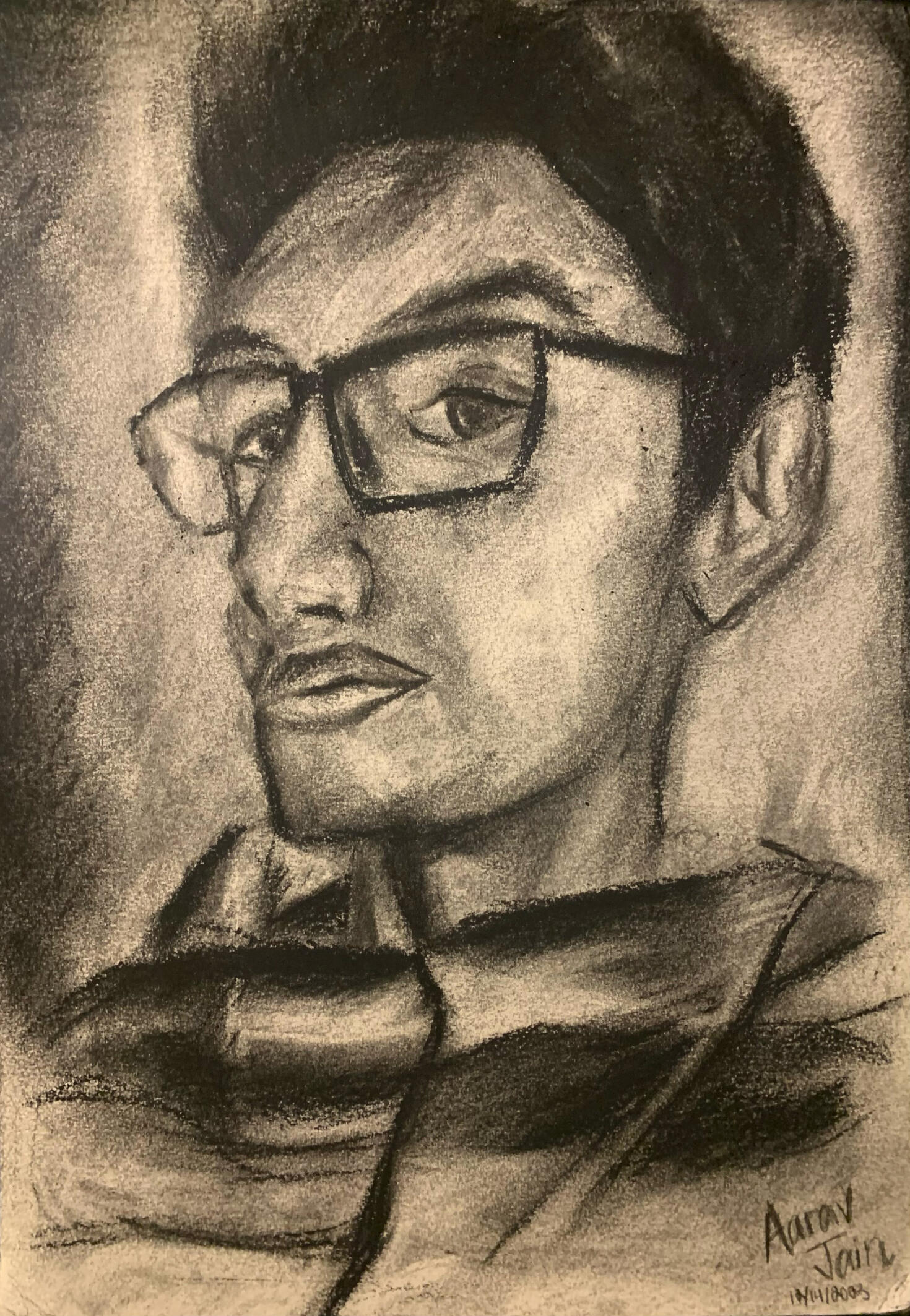

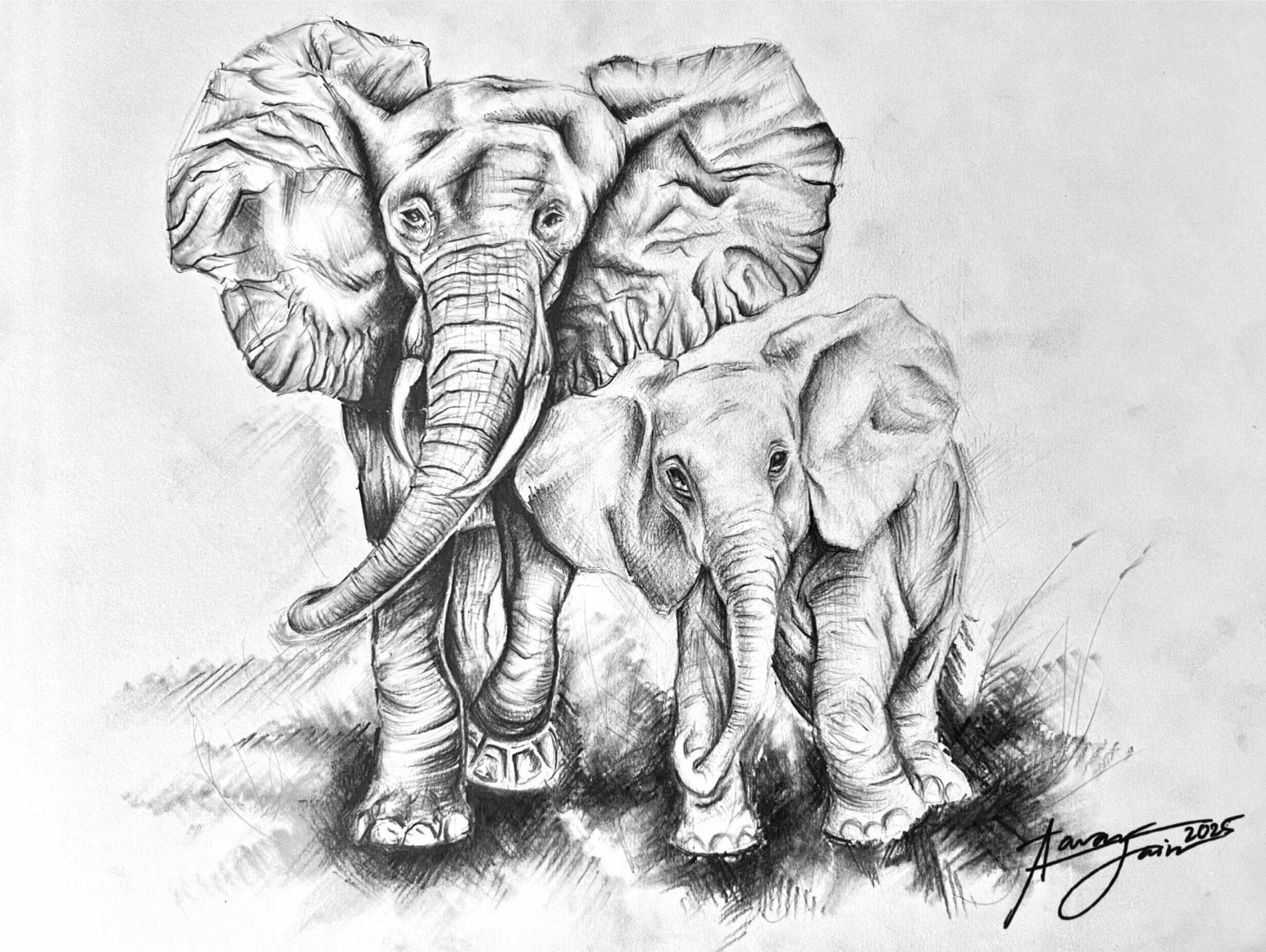

A Fond Memory

A drawing I made for my dad’s birthday. It’s always powerful to reflect on the memory of love, especially between that of parent and child. Parents sacrifice all they have for their children and slowly, the children begin to understand the sacrifice before preparing to make their own.This phenomenon transcends humanity into almost every species. You’ll hear on the news of animals heroically defending their babies. Or just a parent and child adorably enjoying each others’ company. Parental love is eternal, universal, and infinitely powerful, so we should commemorate it each chance we get.

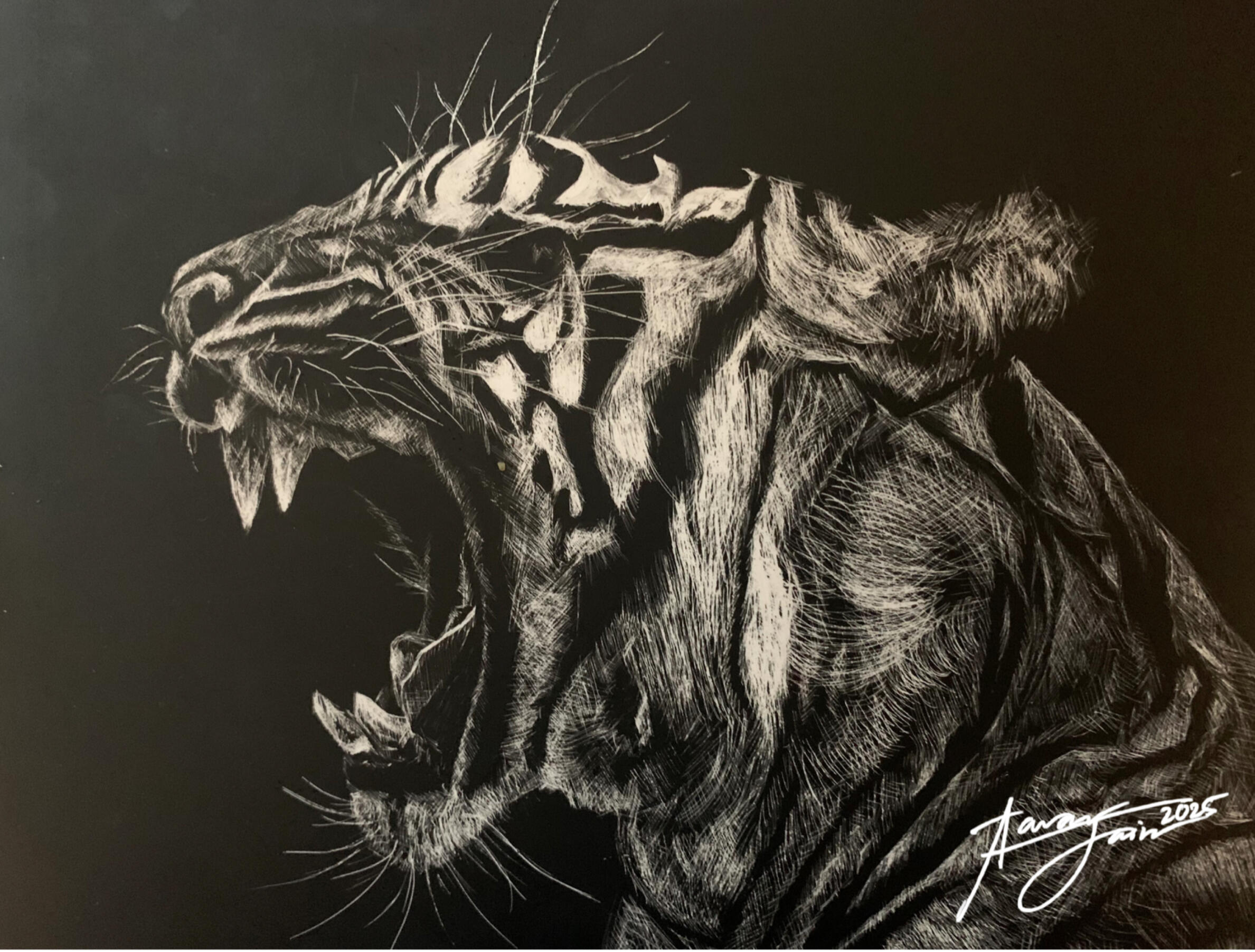

Burning Bright

Scratchboard is the technique of etching/scratching white lines on a black board. As in the process of this art piece, tedious work persisted over time leads to good work.The image of a roaring tiger reminded me of William Blake’s famous poem, “Tyger Tyger”, which opens:Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?The idea of the poem is to reflect on the sophistication of the world. How beautiful is the

piercing, menacing stare of the tiger? As Blake asks in another poem, how beautiful is the

innocent gaze of the lamb? Creation, however it came to be, is incredible. To marvel at creation

is to live life well enough. But being part of creation, we are empowered with our own brilliance.

Just picture a tiger stalking its prey with discipline and concentration. Or a lamb’s innocently

intentioned, gentle nature. That is the beauty of life.So too should we act, with the same intensity towards our truest nature, whatever that may be. In

my unqualified, untested opinion, this includes self-examination, fulfilling duty towards other

things, pursuing truth, and acting extremely in all aspects. Instead, the distraction of the world

dulls and dilutes this purity, leading us towards unimportant things with half-heartedness. If

action is taken with most sincere and pure intentions, like the tiger’s roar, no one will fall short in

their pursuits.

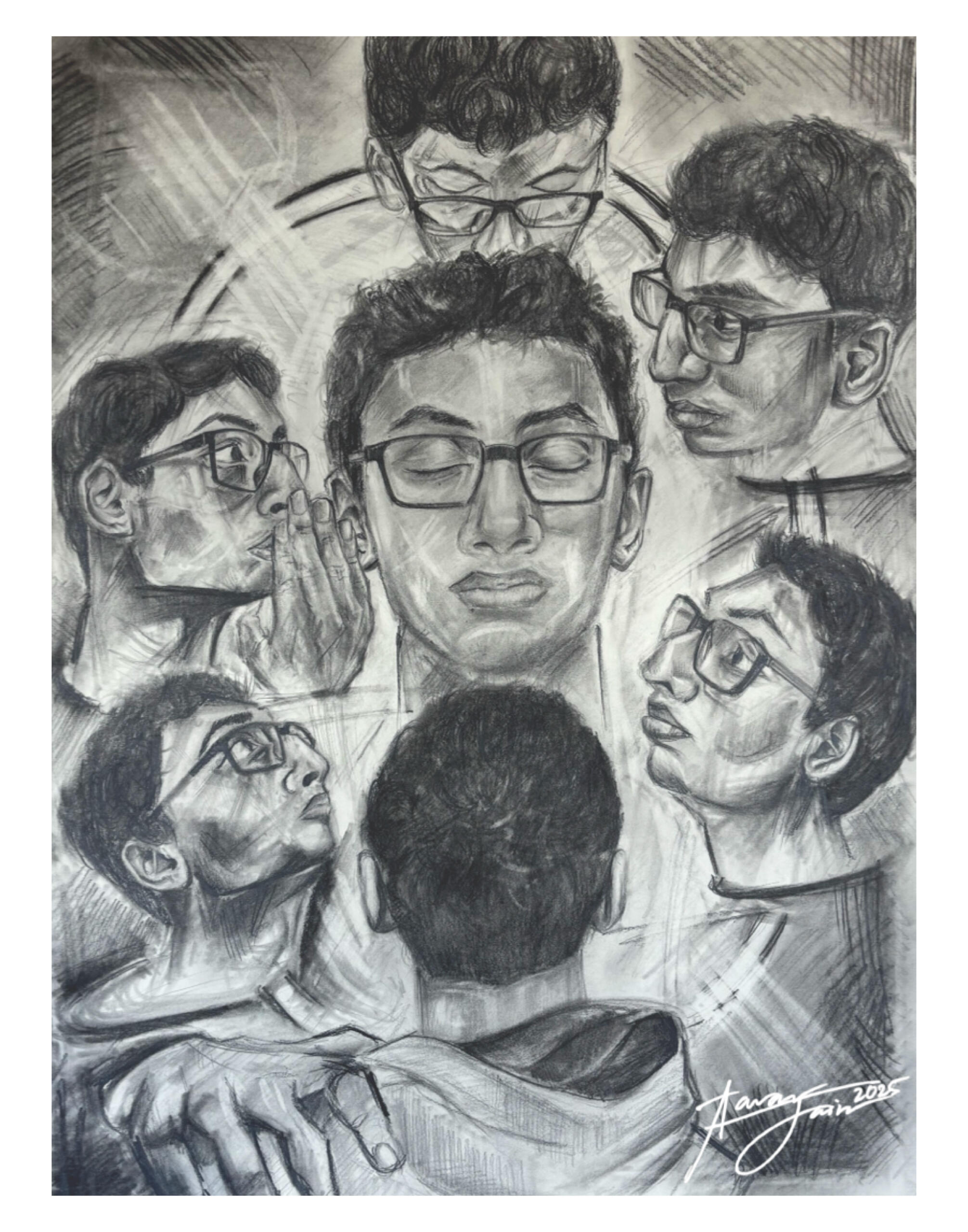

Brainwashed

To my chagrin, I have found inspiration to be a very fickle thing. Which like the moon, waxes and wanes. Inspiration flows unrestrainably at night when I paint, read, and write poetry. Then I wake up and my poems don’t make sense. Sometimes I feel determined to do cardio or lift weights and when the time comes, the motivation is gone. If there is anyone who is not subject to the rise and fall of inspiration, I would love to meet that person.My work, therefore, is symbolic of the flow of inspiration. I picture inspiration to be a waterfall, originating from an external source in arbitrary spurts—much like the idea of cupid shooting his arrows of love. And in the same way love unexplainably grips the mind, inspiration strikes at an untimely moment.Inspiration also, is so abstract and intangible. But inevitably, psychologists or neuroscientists will one day discover the true origin of it. And then, the mystery of inspiration will be resolved by some sort of chemical reaction. Before this day, though, we can enjoy the volatility of our inspiration and marvel at the mechanistic brain’s capability for feeling in the most abstract, delicate, and beautiful ways. The capability to love is more than likely a science. But for those who have been overwhelmed by a feeling of love, it feels so much more than a science. I say it is humanity: the feverish, middle-ground between knowing and not-knowing.So until the day when inspiration is diminished to microscopic activity in some unassuming pocket of our brain, I savor its moments and daily hope for its return. And through a painting made by the grace of inspiration, I can memorialize the beautiful enigma of such moments.

A Lingering Duty

Homer’s Iliad may have been written nearly 3 millennia ago, but that doesn’t make it a primitive piece of literature by any means. In fact, I found that it carried as much emotional weight as any other literary masterpiece. The story is the typical epic—featuring war, feud, superhuman powers—until it isn’t. In essence, the poet Homer created this story to explore the purest forms of human nature: the burning desire for revenge, the tyranny of fate, the choice between legacy and immortality, and more.Within this swirling storm of chaotic human imperatives, the strongest Trojan warrior named Hector is confronted with (in my opinion) the most gripping juncture. As his city is on the verge of collapse, he faces the plain choice: to fight or not to fight. Except, to fight is to fulfill his duty to his vulnerable nation and to flee, to preserve his deepest love for his wife and infant son. Fighting meant near-certain death and fleeing guaranteed the highest shame. Spoiler alert: Hector chose to fight and died, leaving his wife a widow and son fatherless.The scene that appeals most to pathos is the moment before he departs. While his wife protests his decision to no avail, his son watches obliviously. And famously, when Hector addresses his son for the final time, he has to remove the intimidating helmet for his son to recognize the face of his father. Here, the helmet acts as a powerful symbol: the bridge between the frailty of love and bitterness of war. In that moment, Hector must have wanted to stare into his son’s gleaming eyes for the rest of eternity. But the point is, it doesn’t matter what he may have wanted to do. Rather, what he needed to do.The idea that any one of us will face Hector’s exact circumstances is laughable. But in truth, we are all confronted with Hector’s dilemma every day of our lives. We may want to savor the comfort of our bed each morning when the alarm blares and a cold, difficult day awaits us. We wake up anyway. We may seek the pleasure of junk food, social media, and laziness. But sooner or later, we all realize that they have false allure. It hardly ever matters what we want. To put it bluntly, I shouldn’t care what I want, nor should you.Dismissing personal desire is something that scares many people. One may ask, “If I am only meant to follow a specific duty, where is my freedom? Where is my autonomy?” Except, that person is bound by their desires and forced to act upon the smallest urges. That is the person who is not free. It’s humbling, but necessary, to accept that there exist more important things than oneself. For Hector, Troy was more important than him and his family. For me, the ideas of other, wiser people are more important than my own. Therefore, it stands to reason that it is my duty to act upon their convictions, not mine.This concept is echoed across almost every major school of thought across history. I mean, the Iliad comes from Ancient Greece. For Hinduism, almost the exact same scene occurs in the foundational Bhagavad Gita. When the warrior Arjuna hesitates to fight the war after realizing he would have to kill many members of his family, Krishna explains the concept of non-attached work which is intertwined with Hindu Dharma (duty). He says, “You have the right to your work, but never to the fruits of your work.” The value of action lies in performing duty and nothing else.In Christianity, self-sacrifice is central. Kantian Deontology expresses the same sentiment. Although love can be extremely powerful in abstract ways, historical wisdom prioritizes duty. Not because duty is better or more powerful or even more valuable, but because duty is duty.Ask yourself the same question: to fight or not to fight? In my life, the equivalent might mean moving away from home, which already feels unbearable. But then I realized: the pain of doing the duty is also the greatest evidence of love. Just think of Hector, savoring the last moment with his son, before donning his helmet and facing impending doom. Is that not the greatest act of both duty and love?

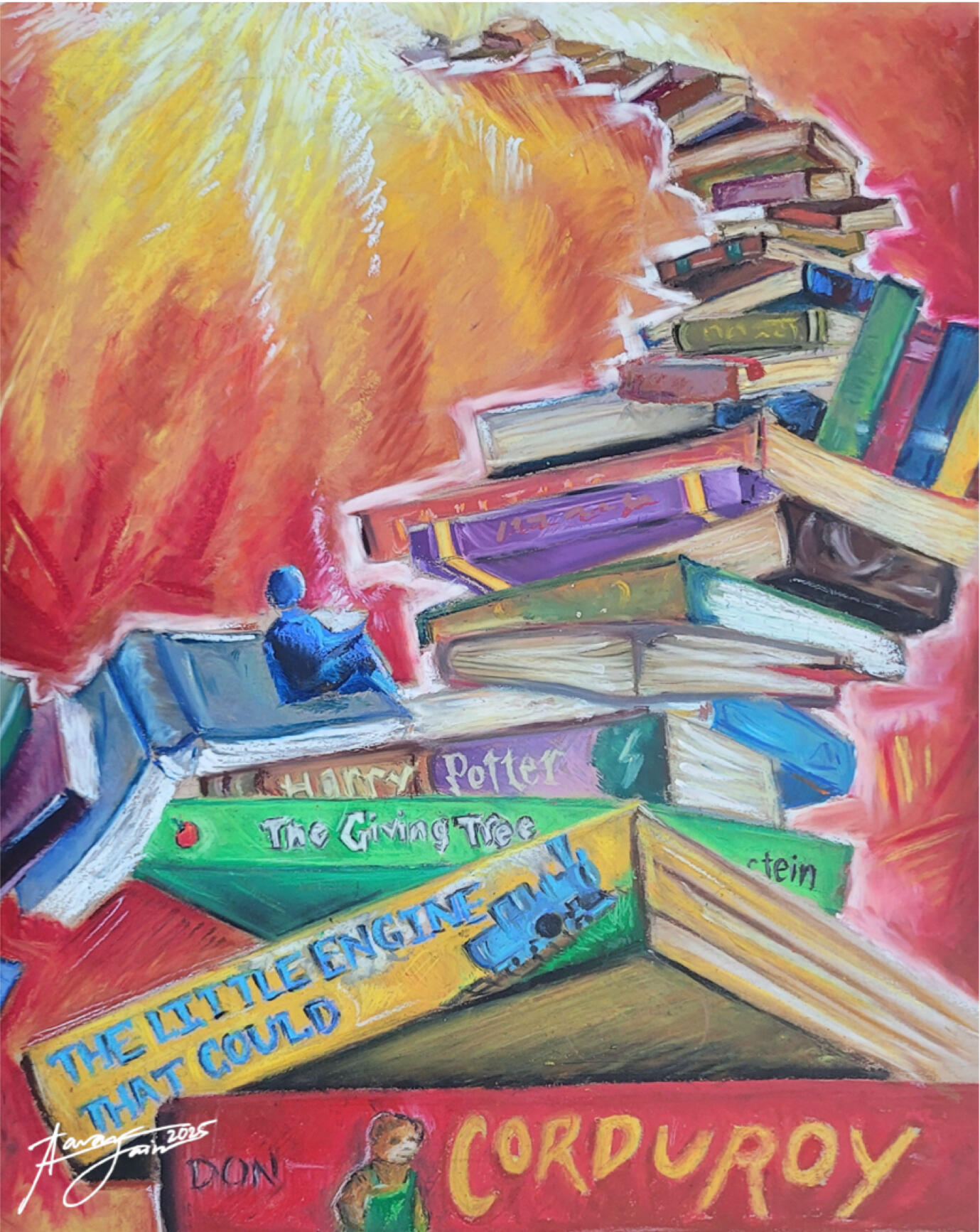

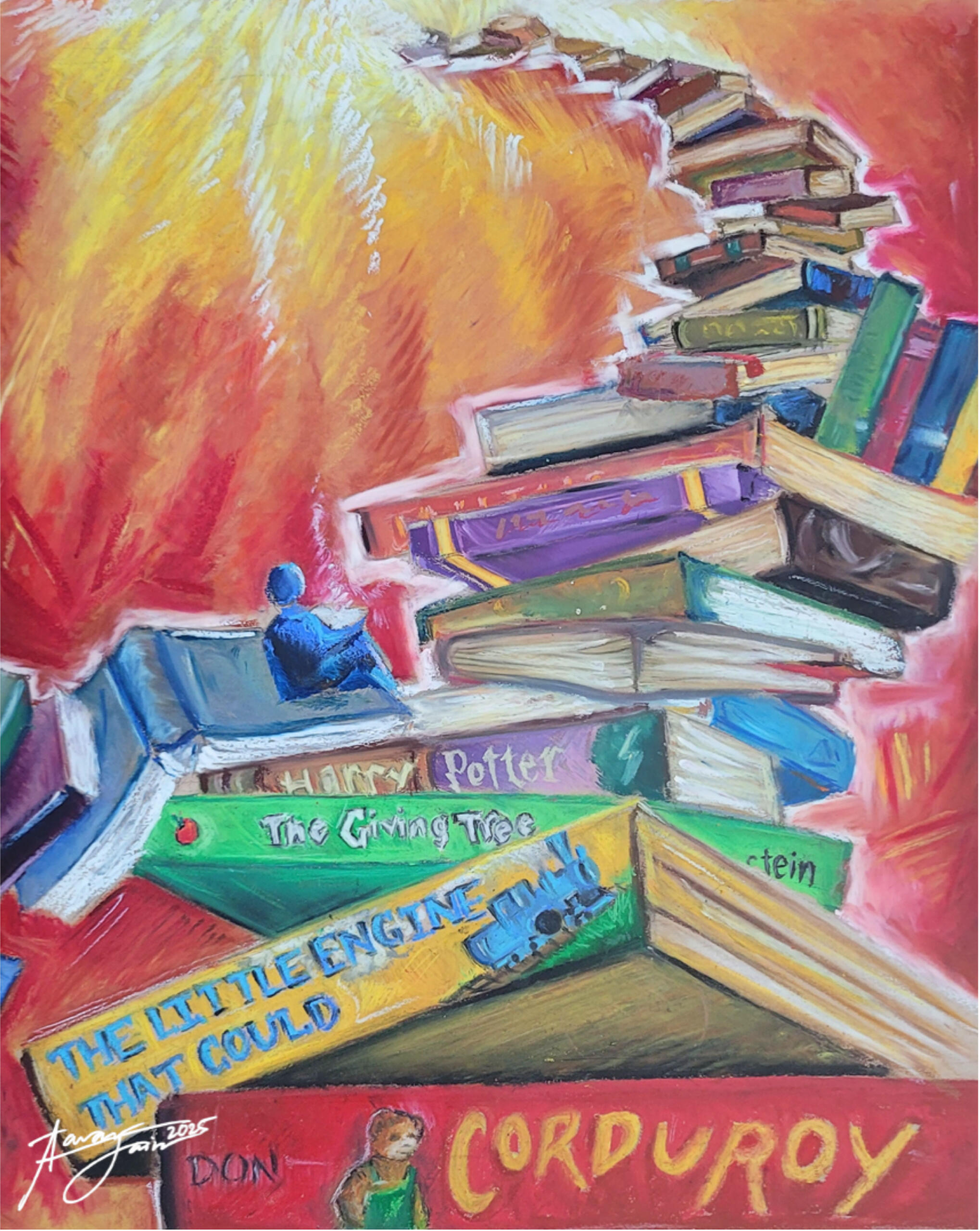

The Ascent

The visual of an uphill journey has always inspired me towards action. The Greek mythological figure Sisyphus was eternally cursed to push a boulder to the top of a hill each day, only for it to come tumbling down the hill by the next. Famously, the French philosopher Albert Camus redefined Sisyphus’ efforts as purely fulfilling, even if it bore no practical result and demanded eternal struggle. Since then, the concept of upward struggle has motivated my own pursuits.One such pursuit, as depicted in The Ascent, is the intellectual journey towards wisdom, truth, and maturity. The very action of reading and consuming knowledge always feels rewarding, regardless again of the practical result. Thus, the object of my work was to remind myself of this noble but difficult journey in the hopes of undertaking it more consistently.The childhood books mark an introduction to reading and learning. Corduroy is the first book I remember reading and slowly but surely, my selection grew. The Little Engine That Could is a timeless reminder of motivation and The Giving Tree, while defined as a childhood book by nature of its simplicity, felt infinitely more meaningful when I revisited it about a decade later. The legible titles end pretty low on the bookstack. This is partly because I couldn’t add small enough lettering to the small books and partly because I don’t know what exists higher up.Broadly speaking, the bookstack’s design subtly resembles the shape of a question mark. Especially in learning, curiosity is a prerequisite. The top of the bookstack disappears into a brilliant explosion of light—symbolic of the enlightenment or clarity gained through learning. Today, I am reading Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky, which is quite a ways away from Corduroy only some years ago. One day, I hope to be further along this metaphorical staircase, absorbing deeper truths with deeper sincerity. But regardless, it is the very intent to seek higher meaning that makes us human. The fact that we make the conscious decision to ascend the staircase is enough. As Camus wrote, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

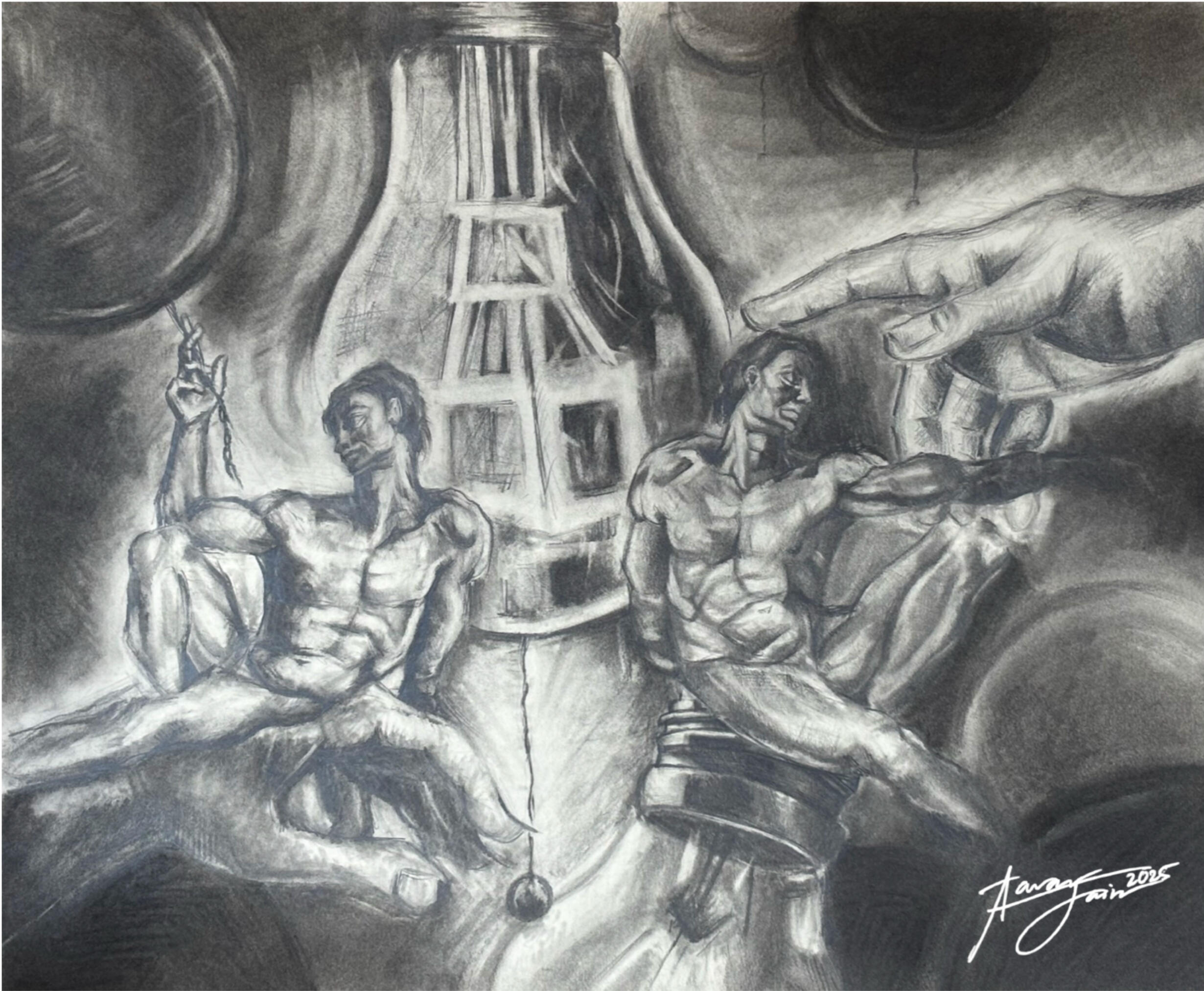

Enlightenment

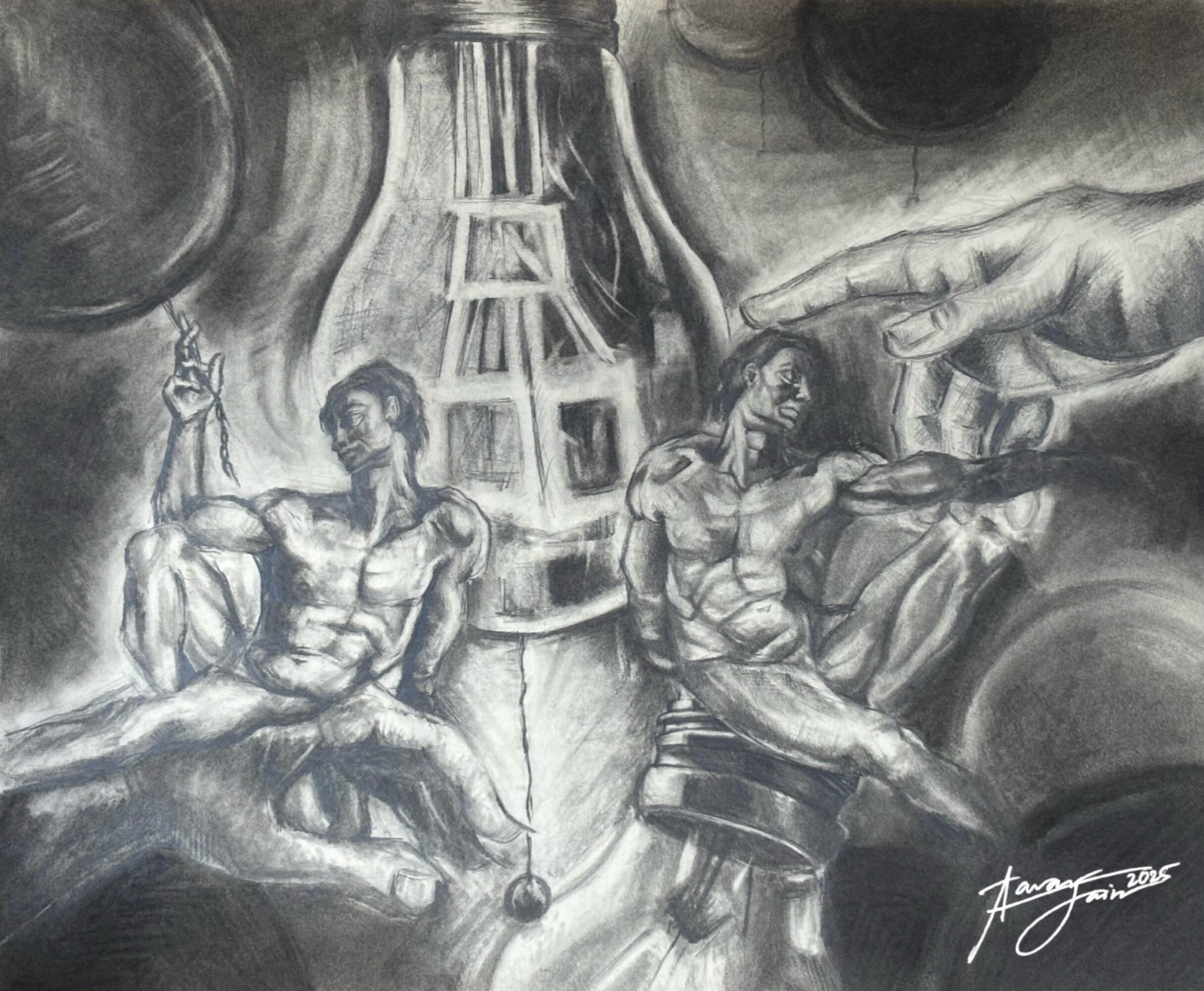

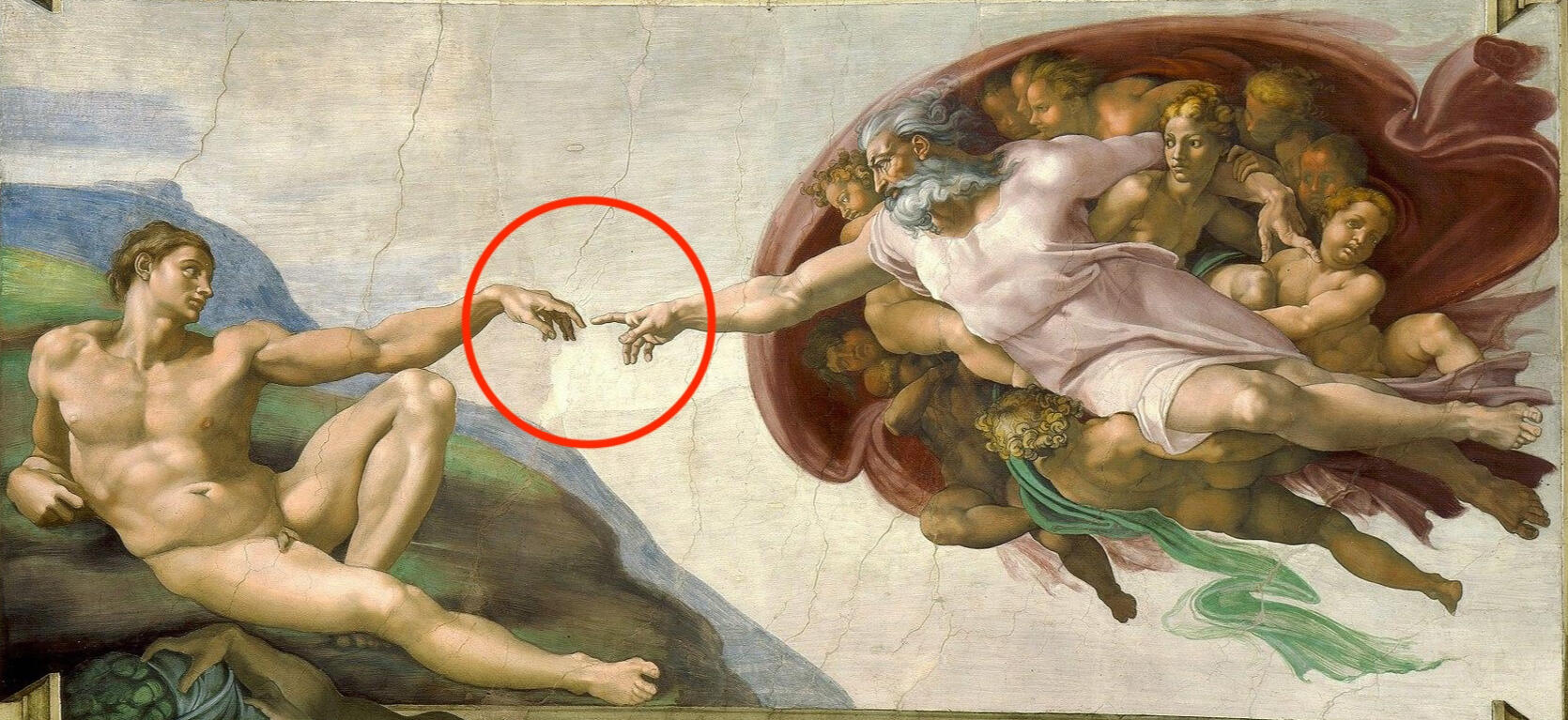

The principle idea of this drawing comes from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The Renaissance master Michelangelo devoted four years of his life to painting the ceiling, an effort that has since been considered the pinnacle of art. And yet, out of all the brilliant designs found swirling across the ceiling, one image has persisted in a state of higher fame. This image, called the Creation of Adam depicts the biblical account of God first creating man. The hand of God reaches assuredly towards Adam, inviting man into relationship. However, Adam doesn’t reciprocate and leaves his hand stretched only feebly in response.

This gesture to me, though subtle, illustrates the shortcoming of humanity. Somehow, in spite of all our ambition and resolve to be good, there always seems to come a time when inspiration dries and clarity disappears. Idleness eats away, mistakes are made, and regrets fester. Alexander Pope put this painting to words, saying “to err is human; to forgive, divine.” This is the heart of my drawing, the rest only embellishment to convey the concept more elegantly.In my artwork, the figure of Adam (man) is inverted, leaving opportunity for symmetry and contrast. Similarly, two hands appear, in the top right and bottom left. Light is used as the archetypal symbol of truth, goodness, and man’s brilliance while darkness represents shortcoming. In a phrase, my drawing is about the flickering of man’s light.On the right half of the piece, the hand of God beckons man to turn towards the light. But man ignores in his typical, stubborn, irrational way, and dangles out toward the darkness. This is the typical interpretation of Michelangelo’s work as well. On the left half, though, the opposite unfolds. Man reaches out to switch on the lightbulb while the lower hand cuts the central cord of light with its fingernail.Suffice it to say, there is a constant internal battle between opposites: action vs. inaction, social vs. contemplative, and of course—good vs. evil. To me, this is (and always will be) fundamental to being human.

The Giving Tree +

Meditations

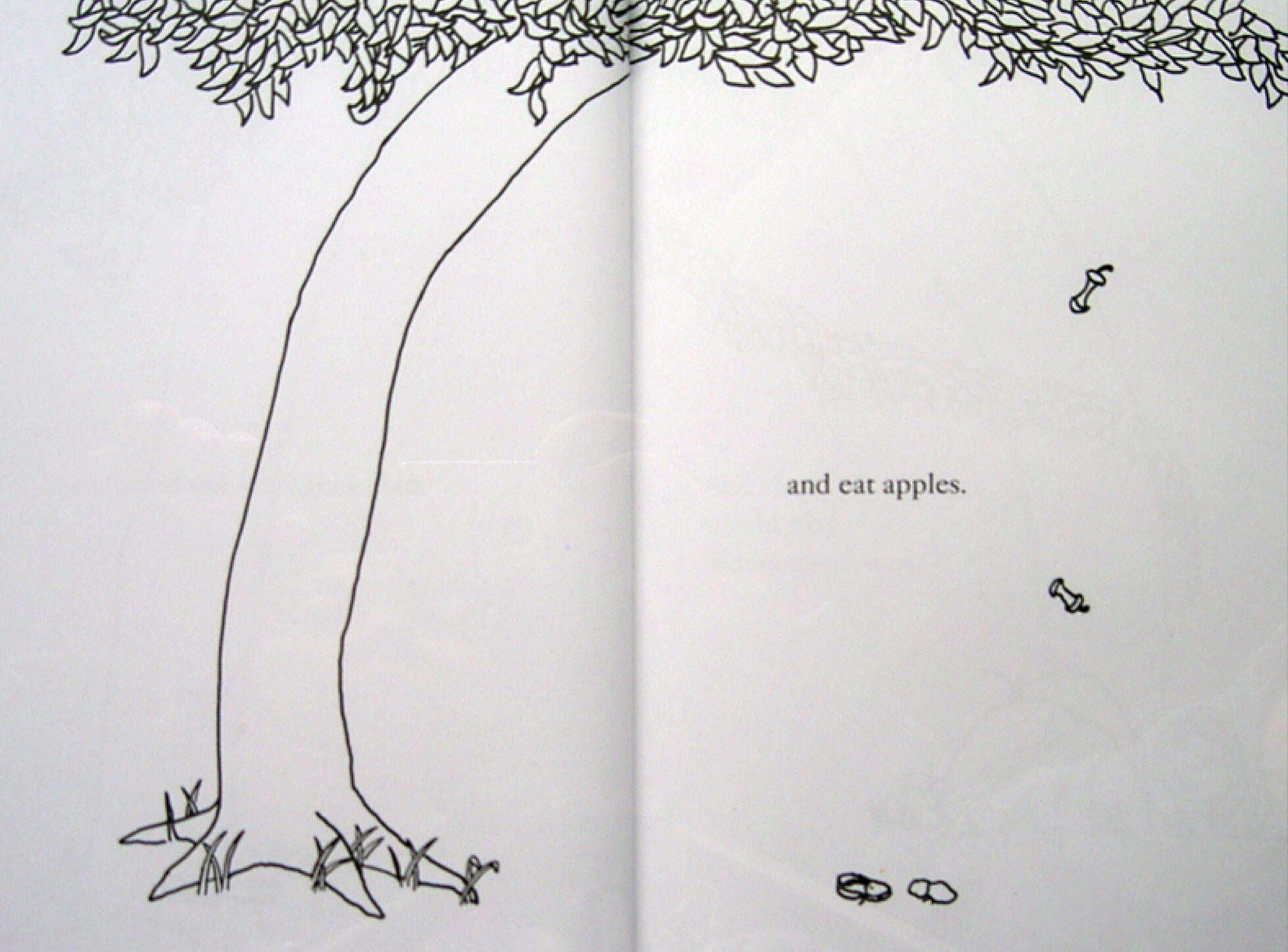

Oftentimes the simplest things hold the deepest meaning. If you’re unsure, read The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein. When I first read it, at around 5 or 6 years old, the appeal was obvious. It had a bright-green cover, cool illustrations, and straightforward writing that invited the young me to flip each page and fly through the book. However, it always left me unsettled by the seemingly sad ending. The tree was gone and the boy was old. But I was young, and naive, and never spared the book a second thought.Exactly 10 years later, I was drawing the design for another artwork—The Ascent—and had to include a few childhood books to illustrate the beginning of my reading journey, including the nostalgic book by Silverstein. Only then did I return to resolve the unsettling ending and by the end of reading it again, it felt like I had read a new book altogether. Each drawing spoke volumes in its subtlety, as did the painfully straightforward plot. Seriously, the final image of The Giving Tree may well be the most powerful reading experience I’ve ever had. Preserving a reminder of this beauty in a painting was reason enough to paint.From this newfound discovery of depth, I set out to paint two scenes to summarize my takeaway from the book:1) The Giving Tree: The first scene is inspired by the early, idyllic stages of The Giving Tree. The boy plays freely, swinging from the branches and eating apples, unburdened by the impurities of society. The tree observes with a more mature contentment. Silverstein’s image below was the direct inspiration of my design, with the subtlety of fallen apple cores conveying the story adequately. The rope ladder suspends, bearing traces of the upward reaching climb in The Ascent. When we look back someday, this painting should symbolize the “Good Old Days.”

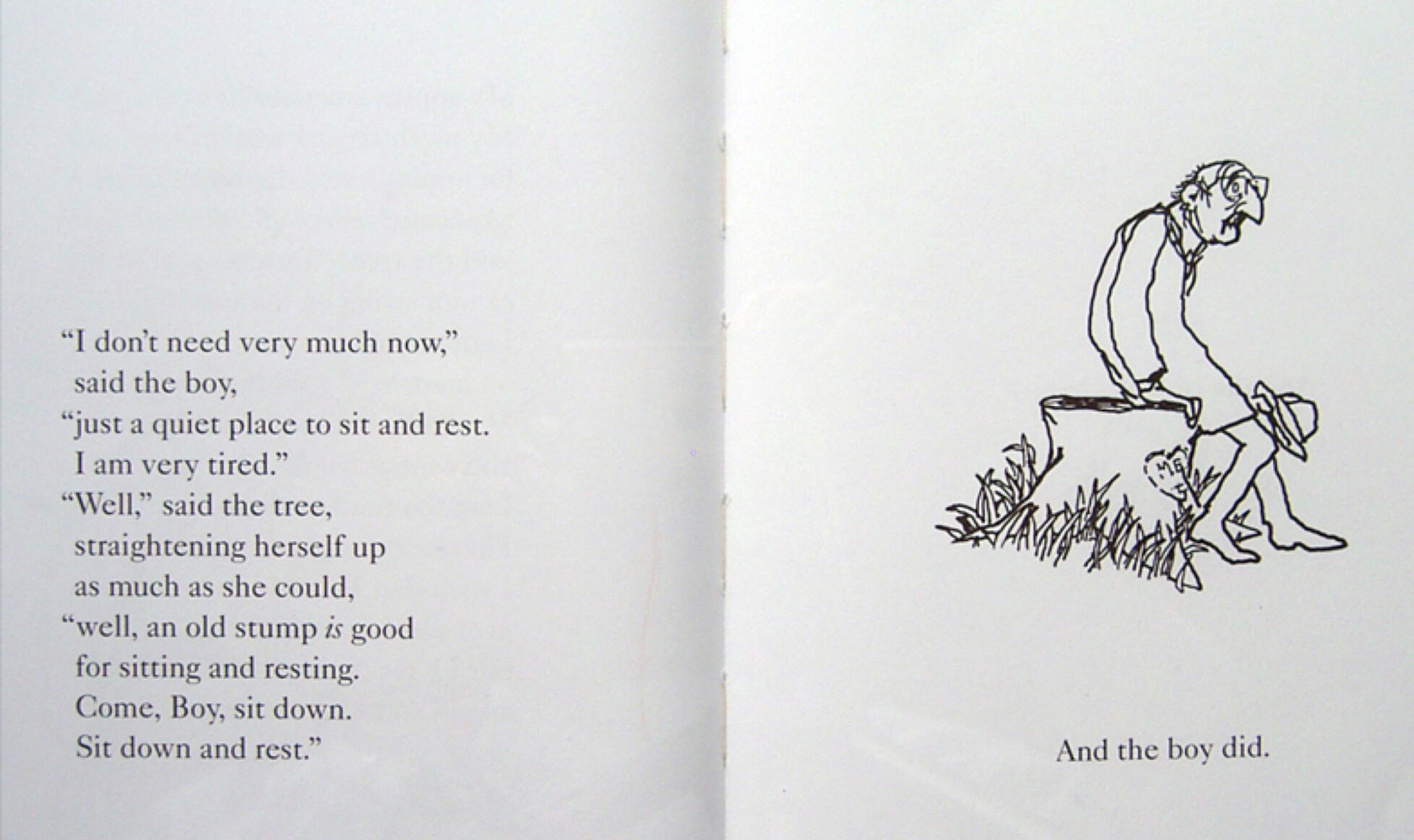

2) Meditations: Shel Silverstein’s book is one of the most elegant depictions of the frailty of life. It’s quite simple in theory to comprehend that “time and tide wait for no man”, and that life will pass by regardless of how we choose to spend our time. Of course though, it is a very difficult truth to accept. Especially when existence is all that we know, and we are cursed by habit to only appreciate the moments that have passed. In my painting, an elderly figure meditates on the stump of a tree, commemorating the colors of life and making peace with the bleak nothingness of death. I used to feel deeply bothered by death. After reading The Giving Tree, I realized that death only makes life taste sweeter.

I can only aspire to someday reach Silverstein’s level of creativity to convey the most beautiful truth in the simplest, most accessible form. For now though, here is a poem I wrote about the same concept of frail fleetingness of life, written as if I was reliving my life from the end to the start. The titular Magnolia Lane references the drive into Augusta National—the most prestigious golf course in the world. I find that playing a round of golf is similar to life: most exciting in anticipation, quick to pass you by, and leaves you wishing to relive it by the end.Memory? No… Magnolia LaneWe always start at the beginning.

At sunrise.

But what if—

What if we watched the dying candle grow?

And stagnant waters start to flow.

And the wise man forget to know,

Gladly.Isn’t there something to oblivion?

To innocence?

Something that stops a tired heart—

Makes it flutter.

There is life to living,

But there’s life in reliving as well.It would be nice to forget the things

We never knew.

Less painful, at least.

Fall after Winter.It would be nice to return to the start,

Sunday mornings streaming sunlight.

It would be nice to return to it all;

Drive back down Magnolia Lane,

And die in the arms of an awaiting life.Wouldn’t it be nice to go back?

To last a lifetime?

To last lifetime.

To last year.

Last month?

Yesterday?One day, it would be nice to return to today.

The good thing is,

We can—But just for now.